By Chou’s Side

Victoria Kao sits in Chou Tien Chen’s corner during his matches. While the action is on, she is his chief supporter, egging him on; during intervals she sprints to his side and hands him whatever’s required – a drink, towel, change of shirt.

Her main role, however, is keeping him in peak physical condition – for she’s his physio.

It is unusual for a top player to have his physio rather than his coach courtside, but Chou is unique in this respect. The world No.2 is the only top player from a badminton powerhouse to rely on his own wits for tactical adjustments; considering that he just won two tournaments in three weeks, the approach seems to be working. It’s an approach that makes him and his small team stand out in the circuit, for nearly every other top player is seen deferring to the instructions of a personal or team coach.

The other exceptions in this regard are Michelle Li and Beiwen Zhang; with them, however, the issue is (or was) mainly of funding. Chou prefers not to have a coach because he believes the solutions to his on-court challenges are within himself.

“I need to focus to get a point, so it’s not about a coach, it’s about yourself,” says Chou. “The coach talks to you about your problem. I know my real problem. That is how I improve.”

Instead of a coach, Chou has a sparring partner who has been travelling with him since February. The world No.2 trusts his own reading of the game that allows him to decide training routines.

“We wanted the right person (for coaching),” says Kao. “But after we tried and tried, maybe he thought he can play by himself. He is also a coach, right? That’s one choice. Because he believes in God. He thinks faith can help him to fight. That’s very special,” says Kao, who has been with Chou since 2012.

So what exactly does Kao tell him during the intervals of each match?

“Just encouragement,” she says. “I ask: ‘Do you want to change your shirt?’ ‘Want to eat something, or have a sports drink?’ I’m a physical therapist, not a player. The reason why he wants me in the seat is because he can focus. I’m always quick to finish my service, so that he has more time to think about his game.”

Chou, compared to his contemporaries, has peaked late. He is 29 and having the season of his life. His performance in Indonesia was epic. He outlasted younger challenger Anders Antonsen in the 91-minute final after having spent an average of 76 minutes on court in each of his previous three matches. That he won the Thailand Open in the next fortnight is a tribute to his physical and mental fortitude.

“Every day we do a lot of repair on his body,” says Kao. “Physically, he is improving. Just a little, step by step. Repeat and repeat. Very slowly, very slowly, but he’s getting better.

“He’s getting better mentally. There’s still a lot of space to improve. Every day, we find one problem and set it right. We think even if we can improve by 1 per cent, we will do that. We need to improve, not stay here. Many young players are very strong, very fast, so we need to stay humble. He is 29, but he must be like a young player, keep learning.”

Perhaps the most arresting image from Chou’s epic Indonesia Open win was Kao and Chou crying a flood of tears. Kao is thankful for his win, but is already looking ahead.

“It was a beautiful treat, a beautiful experience. (But) It’s closed and finished. This week we should focus and start again. We can’t depend on that memory. Be happy, but stay focussed, pay attention.”

World Championships News

Lessons Learnt, Parting Perspectives 14 September 2019

Kidambi Srikanth – A Search for Form 13 September 2019

Momota, in the Eyes of his Opponents 12 September 2019

Recap: Upsets at the World Championships 10 September 2019

Recap: Memorable Matches of the World Championships 8 September 2019

Highlights of the World Championships 7 September 2019

Played ‘Two’ Perfection – Basel 2019 4 September 2019

Badminton, Ice Hockey and the World Championships 4 September 2019

Three-Event Titan – 25th Edition World C’ships 3 September 2019

Legends of ’77 – 25th Edition World C’Ships 31 August 2019

Para Badminton Event Comes to a Close – Basel 2019 27 August 2019

Wristy Trickery Wins the Day – Basel 2019 26 August 2019

Great Comeback Falls Short – Basel 2019 26 August 2019

Mixed Doubles ‘Great Wall’ Intact – Basel 2019 26 August 2019

Antonsen Bows to Momota’s Class – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

Gold – At Last! – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

Poveda Makes It a First for Peru – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

Legend Who Broke Records and Paved the Way for Future Stars –... 25 August 2019

Ray’s a Real Sport – 25th Edition World C’Ships 25 August 2019

China Take Two Gold – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

‘Upsetting’ Night for China – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Antonsen’s ‘Insane’ Dream – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Glasgow ’17 on the Cards – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Five Down, Seventeen to Go – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Sindhu Assures Herself: Tomorrow Will Be Different 24 August 2019

Para Badminton Athletes Turn It Up a Notch – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Flaming Dane Set Courts Aglow – 25th Edition World C’Ships 24 August 2019

Antonsen Delivers for Europe – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Du/Li Stand Tall After 2-Hour Epic – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Kantaphon Leads Thailand’s Record Haul – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Sensational Session for India – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Tall Order for Standing Men – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Crowd Pleasing Superstar – 25th Edition World C’Ships 23 August 2019

Teenage Shuttler Meets His Idol – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Wheelchair Top Seed Toppled – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

‘Two’ Much Trouble! – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Intanon Survives Scare – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

BWF Statement – TOTAL BWF World Championships 2019 22 August 2019

Belated Birthday Blitz! – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Back Problem Doesn’t Stall Jia Min – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Girl Power – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Group Rounds Move into Main Draw – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Lessons from the Seventies – 25th Edition World C’Ships 22 August 2019

Women Getting in Gear – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

German Shock for Fifth Seeds – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

I Feel at Home says Mroz – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

The Power of the Mind – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

Minions Crash Land at Worlds Yet Again – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

Suzuki Banks on Experience Over Age – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

Nagahara ‘Mixing It Up’ – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Jia Min Ousts Top Seed – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Lin’s Challenge Sputters Out – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Mazur On Track to Retain Crown – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Trading One Set of Wheels for Another 20 August 2019

Ouseph Exits Stage, Bids Goodbye – Basel 2019 19 August 2019

Chou Survives Danish Test – Basel 2019 19 August 2019

A Title Dedicated to a Battle Against Cancer 19 August 2019

Draw Provides an Even Playing Field for All 18 August 2019

Para-llel Event a Unique Experience for Badminton Fraternity 18 August 2019

An Occasion to Cherish for Jaquet – Basel 2019 18 August 2019

‘100 Watt Smash’ that Lit Up Lausanne – 25th Edition World C’Ships 17 August 2019

Preview: Worlds of Opportunity 17 August 2019

Satwik/Chirag to Miss World Championships 16 August 2019

Indian Pair Blazes a Trail 15 August 2019

Awesome Threesome of SU5 – Para Badminton World C’Ships 14 August 2019

Life Lessons, From Coach Kim Ji Hyun 14 August 2019

Free of Pressure, Antonsen Senses His Chance 13 August 2019

Ahsan/Hendra Play it Cool Despite Hot Form 11 August 2019

England Duo Anticipate Fruitful Week in Basel 10 August 2019

Women’s Singles Re-Draw – TOTAL BWF World Championships 2019 9 August 2019

Winny Will Need Support: Liliyana Natsir 8 August 2019

Sports Upbringing Gives Edge to Poveda 7 August 2019

World Championships Draw Released 5 August 2019

Marin, Shi Join Axelsen on Sidelines 5 August 2019

New Para Badminton Chapter Unfolds in Basel 1 August 2019

Injured Axelsen Withdraws From World Championships 31 July 2019

From Malmo to Basel – 25th Edition World C’Ships 30 July 2019

Famous Five and the Good Old Days – 25th Edition World C’Ships 19 July 2019

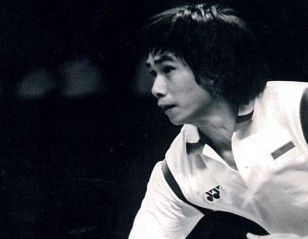

Revisiting a Hero: Sigit Budiarto 11 July 2019

History Beckons Zhang Nan 10 July 2019

Chen To Lead China’s Charge 9 July 2019

19 Days Left To Register for World Coaching Conference 26 June 2019

Marin on the Mend and Eyes Return 22 June 2019

Two Months To Go – World C’Ships Countdown 19 June 2019

Li & Liu – Stepping Up When It Matters 7 June 2019

Ivanov & Sozonov Rekindle The Fire 3 June 2019

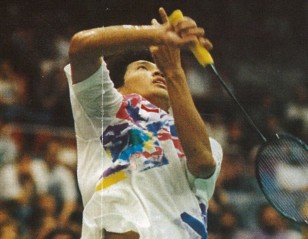

Tien Minh – Veteran Still Chasing His Dreams 2 June 2019

Confidence Boost for Dutch Duo 1 June 2019

Matsumoto & Nagahara: Rapid Ascent to Pinnacle 8 May 2019

Tai Eases into Top Gear 25 April 2019

Zhao Yunlei Star Speaker at Coaching Conference 24 April 2019

‘The Physical Level Has Gone Up’ 22 April 2019

Memories of Lausanne 1995 20 April 2019

Momota Sets the Pace, but Speedbreakers Lurk 18 April 2019

BWF and Total Celebrate Five Years of Partnership 18 April 2019

Badminton Thrust into Bright Lights – World C’Ships 13 March 2019

Gold and Glory for Arbi – Throwback ’95 World C’ships 19 February 2019

GoDaddy Extends Major Events Partnership with BWF 11 February 2019

Star speakers assembled for BWF World Coaching Conference 2019 30 January 2019

Singles Champions – Down the Ages 20 December 2018